Travel Journal, 106

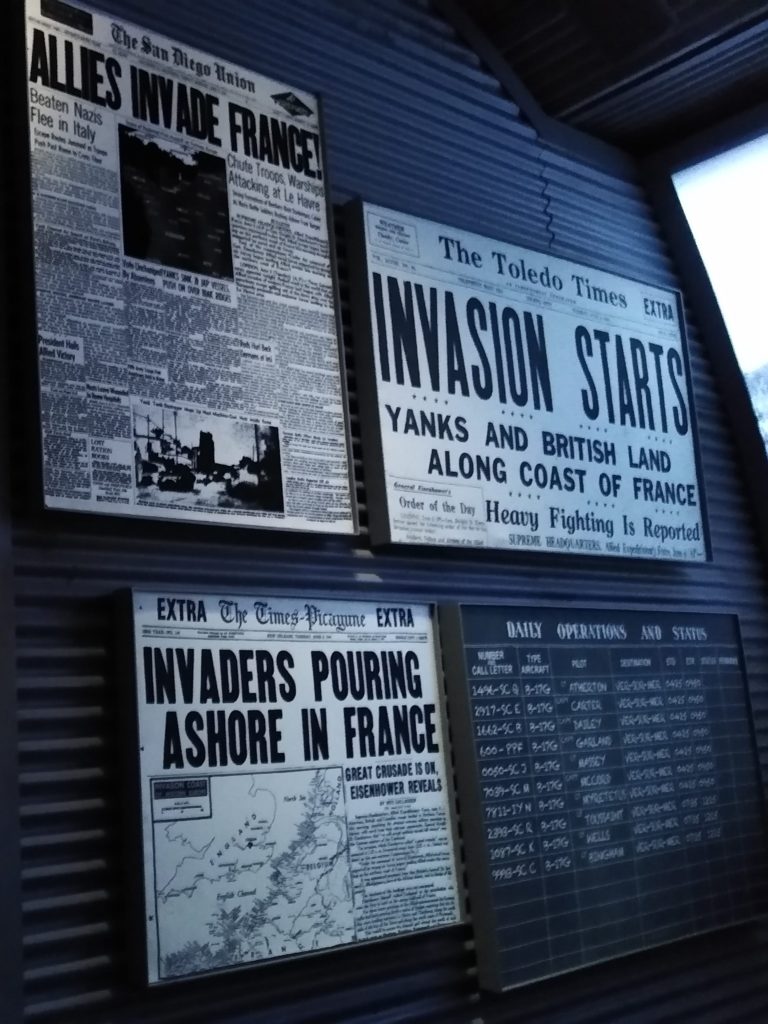

Nobody talks about the second day. We hear mostly about the first day. Sure, June 6th of 1944 deserves attention. The initial landing at Normandy beach in France, that immovable D-Day (codename Operation Overlord), stands in the minds of Americans like a WWII monument.

But what about the second day? What happened on June 7th?

Wave after wave of allied military transport continues to land on the now crowded beach. And not the kind of crowd you’d typically see at the beach. Though some of the bodies had been moved to designated areas, innumerable still lay about the war-stage. Though the sun shines through spotty clouds, a greyness hangs in the air. It looks like a storm is building. Spools of concertina razor-wire jingle as the sea pushes it up the sand, and then back down the sand. It’s not going anywhere. The wire doesn’t float. It just makes a clinking noise and catches Army-green jackets. But nobody can hear the noise. The constant, disorienting rhythm of distant, and not so distant gunfire pummels every eardrum for miles.

It’s amazing how the ocean still holds onto the blood and rubbish of battle. Bodies lay everywhere. The flowing and moving water still just keeps it all close to shore. Guns and barricades and broken implements and empty cigarette packs lie around like a haunting yard sale. The seagulls, apathetic to human plight, seem to be enjoying themselves.

Hundreds, no thousands, of amphibious vehicles landed yesterday. Now, today, many more keep showing up. A boy who lied about his age jumps out of the back of one of those vehicles, and into the freezing water. He wants to be here. Well, he did want to be here. But that’s changing rapidly. His buddies feel the same way. But now they’re very wet, very cold, and very scared. Bullets fling past them at every angle. They are rushing into a fight that they thought they understood. But who understands war? He thought he understood it until the metal platform of that amphibious vehicle slammed into the sea, and an ugly scene of the real face of war lay before he and his buddies. A lot of his buddies, and maybe him, will be dead within a few days. Maybe this day. And he knows it. So he holds his rifle close to his chest and pushes up the beach with the other men. Nearby, a commanding officer shouts orders and action-plans. But he can’t hear his CO over the waves and the gunfire and the beat of his own heart. A seagull squawks, fighting another seagull over a bloodied bandage. Unheard razor-wire sloshes in the waves.

How long is this going to last? They’re told the Allies are “winning.” But what does that mean anyway? How can this be what it looks like to win? But deep down, he still wants to be here, in Normandy, France; fighting for the freedom of not just Americans, but for those under oppression. There’s talk that Hitler has prison camps that some call “death camps.” It’s a place for Jews, and Catholic priests, and homosexuals, and political foes, and everyone else that the Third Reich thinks unclean and unworthy of humanity. But those are only stories he hears. Only time will tell the truth. If only this war could end. So he fights his way up the beach further to the next barricade, to the next assignment, and, later, on to the third day of the landing at Normandy beach. They made a lot of headway yesterday. But today, the 7th of June, the second day of the D-Day invasion, the fight continues…

Of course, I wasn’t there. I’m in my mid-thirties, sitting at a kitchen table writing about a topic I can barely broach. D-Day took place 77 years ago. Admittedly, I didn’t even really research anything. I have no idea if that’s what it looked like to be there. I made it all up.

Or did I?

I don’t know about you, but WWII history intrigues me deeply. History in general takes up massive hard drive space in my brain. But what you just read about the second day at Normandy was complete fiction.

Or was it?

Sure, I set the scene and painted a picture. I can make educated guesses as to the nature of waves and seagulls. I wasn’t at Normandy, and I’m certainly no historian. But I have been influenced, just like you and everybody else in this country, by the history taught us and the people who lived it. We are influenced by the living memories of others and the fruits of their labors. However, the fact remains that I simply wasn’t there. We rely then, on those who came before us to teach us through story and memory.

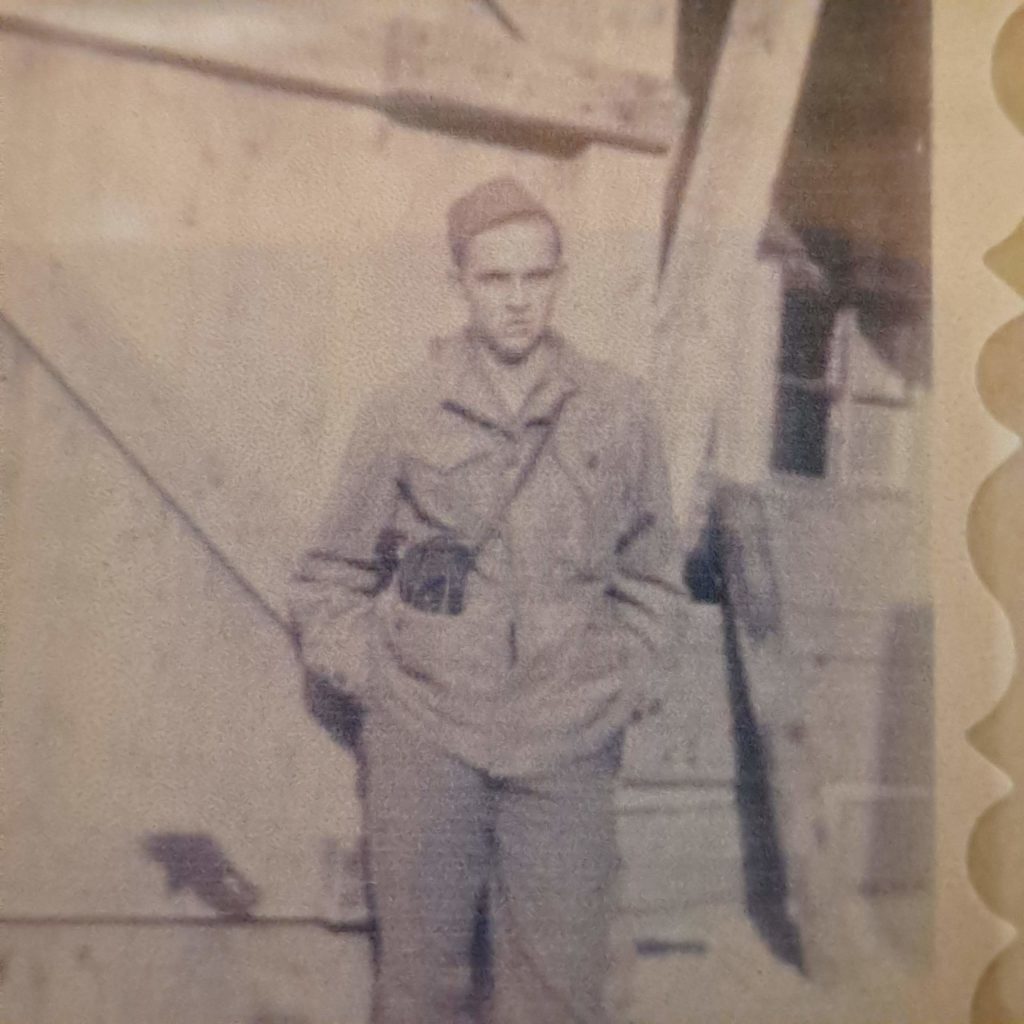

My great-grandpa, Donald Butler, like many other American grandfathers, fought in WWII. In fact, he actually did land at Normandy beach on the second day of the invasion. I don’t know much about his time there. I never asked him about it. That’s one of the many topics I wish I would have asked him about before he died. But I remember him and I remember the history enough to at least think about what it was like. According to my great-grandma Jean and my Grammy (their daughter, my grandma), he was with the second wave at Normandy, and trucked supplies all over the country. I’ve recently been thinking about Great-Grandpa Don and his stories, his contributions to the National Memory that continue to build a post-WWII world. Like the time he almost ran over General Patton. Or the time that he shot all the lights out of the barracks, much to the chagrin of his Sergeant. But most of all, the time he landed at Normandy beach on the second day of Operation Overlord. He and the story of Normandy beach have influenced my thinking and existence to a fundamental level.

I recently thought about Grandpa Don while I walked through the labyrinth that is the National WWII Museum in New Orleans, Louisiana. If you happen to make it to The Big Easy, ease your way pass the French Quarter, pass the cheap booze, and pass the souvenirs. Do yourself, and mankind, a favor. Go to the National WWII Museum. Educate yourself, teach yourself, and remember. Wall after wall of relics, history, uniforms, weapons, and war paraphernalia lay out a story of heartbreaking truth. And guess what? It’s not just their story.

It’s your story. The people who fought during that time, formed this time—the time in which you live right now. It’s all the same story. This is why we study history and are drawn to the true tales of our grandfathers.

One of the exhibits at the National WWII Museum is called Dimensions in Testimony. Men like my Great-Grandpa Don have stories that need telling. The Shoah Foundation sat with several of these men and talked for hundreds of hours, recording their oral history and experiences. Through the use of artificial intelligence, an interactive, programed recording can have a “conversation” with the museum-goer.

The screen in front of me displayed a man sitting on a chair. I pressed the button on the podium microphone and asked a question, “what was it like seeing the prison camps for the first time?” The picture moved and the recorded man began to talk and tell me of liberating the prisoners.

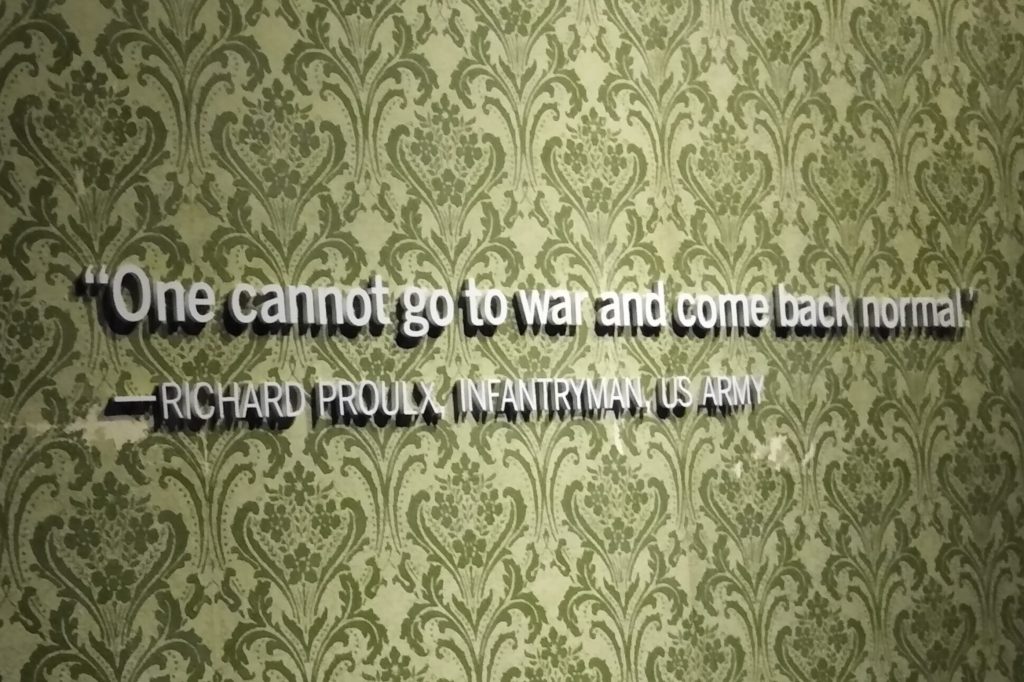

A famous quote says something about being doomed to repeat history if we don’t learn from our past. It’s a tight and nicely packaged saying that strikes a chord with most people. It suggests that we learn from our past to build our future in a better way. But history, such as D-Day, does not influence our future. I can’t change the future—nobody can. It hasn’t happened yet.

History informs us on how to live in the now—in this time. It’s active, alive. Learning WWII history, hearing a story, or see a museum could dislodge an emotion or thought, rewire your brain, and make you live differently.

You may go to a museum. You may see pictures of Dachau or Auschwitz—sunken, sullen people with rags hanging from their bodies stand looking glumly at the camera. You may think to yourself, “that’s a person. They did that to a person.” You may leave the museum and find yourself treating people with a bit more kindness. History changes us in the now.

I may not have been on that beach in Normandy, France on June 7th, 1944, but my great-grandfather was. And maybe yours was too. Their stories and experiences shape how we live. Those who don’t learn from history may or may not be doomed to repeat it. I don’t know. But if you have a chance to go to the National WWII Museum, I can promise you a better understanding of the story in which you live, and maybe even a slightly improved world.

Or better yet here’s an idea, if you can, talk to your great-grandparents. Boy, do they have stories for you.

anthony forrest